Pachaiyappa Mudaliar, the most munificent patron of learning and religion in modern south India, was born in 1754 in Periapalayam, a village about twenty five miles from Madras, where there is famous Sakthi temple.His father, Visvanatha Mudaliar, had passed away a few months before and he seemed born to destitution and misery.But by dint of unexampled commercial acumen, always regulated by honesty and fairness, he amassed a huge fortune in only forty years, when he passed away in 1794.It was with his money that the first Indian College in Madras was started and, along with it, a number of other educational institutions which keep his memory green.

Pachaiyappa Mudaliar, the most munificent patron of learning and religion in modern south India, was born in 1754 in Periapalayam, a village about twenty five miles from Madras, where there is famous Sakthi temple.His father, Visvanatha Mudaliar, had passed away a few months before and he seemed born to destitution and misery.But by dint of unexampled commercial acumen, always regulated by honesty and fairness, he amassed a huge fortune in only forty years, when he passed away in 1794.It was with his money that the first Indian College in Madras was started and, along with it, a number of other educational institutions which keep his memory green.

Visvanatha Mudaliar, an Agamudiya Vellala, has been living in Kanchipuram, the great city of Tamil antiquity and heritage, in quite humble circumstances.He and his wife, Punchi Ammal, had two daughters, Subbammal and Acchammal, before Pachaiyappa was born.Visvanatha Mudaliar’s death, apparently in prime of life, was a great blow to the bereaved family.The mother, along with her two children, virtually took refuge in Periapalayam.There she had the good fortune to earn the esteem of Reddi Rayar, who was Faujdar of the Periapalayam District under the Nawab of the Carnatic.It would seem that Visvanatha Mudaliar and Puchi Ammal used, before the later settled down there, to visit the village for the famous festival and that they had made friends with the Faujdar. It was there that, in a few months, Pachaiyappa was born.

For some five years the family was able to live in fair comfort, mainly because Reddi Rayar (the name sounds strange, but it was not uncommon at the time, for another man of the same name was involved in the imbroglio of the debts of the Nawab of the Carnatic, Mohammad Ali; the correct form of the name seems to be Reddi Rao) and his wife, Venkatammal, befriended the helpless family out of old friendship.Then tragedy struck again.Reddi Rayar passed away, and the family was again left adrift.Venkatammal and some other friends in Periyapalayam continued to help it, but Puchi Ammal resolved to remove to Madras, to the “Black Town’s” as George Town used to be called then.The family was able to obtain a place of residence, a small house, at the northern end of a lane called Swami Maistry Street, near Walltax Road.(Another source of information says, near the Esplanade.Here the nearly distraught mother was fortunate enough to obtain the help of “Powney” Narayana Pillai, of Neidavaya, through a neighbour, who was an employee of that magnate. Since this kind and helpful Indian leader of the times was greatly instrumental in Pachaiyappa developing into multi-millionaire, it is necessary to explain what he was and the conditions of his time.

In 1760, when Pachaiyappa first came to Madras, hardly a year had passed since, for the second time, the French had besieged Fort St.George, but this time unsuccessfully.Count de Lally, maddened by the failure, had retreated, wreaking destruction along his path.The victorious British were beginning to rebuild the fort into something very much like what it is today.But the debris of the ineffective siege would be still strewn about, and young Pachaiyappa would have seen what war meant to people.

He would, of course, have been for too young to understand the political and economic conditions of the time.These were pretty chaotic.The Nawab of the Carnatic, Mohammad Ali, was nominally ruler of a vast territory extending from Nellore to Tirunelveli. The real rulers were the British.In the Carnatic wars, they had defeated the French.The French siege of Fort St.George was an incident in the second war.

The inhabitants of the “Black Town” had felt war’s alarms.Very near where Pachaiyappa was now living, a skirmish had occurred on December 14, 1758, hardly two years before he had come to live in Madras.Colonel Draper had a brush with a French contingent.There was some street fighting in this war, and the “Black Town’s” appearance could not have been much improved thereby.

The young boy must have heard some of the older residents talk about the stirring events of the first Carnatic war when, in 1746, on the banks of the Adyar river, a tiny French contingent, marching from Pondicherry, had made short work of a huge array of the Nawab’s, about de la Bourdonnais’ siege of the fort, about the British surrender after only two days of nominal resistance.He might have heard but probably could not have realised the significance, of the exploit of Robert Clive when, with a small force, he held at bay, in Arcot fort, a huge army of Chanda Saheb who, under French auspices, was fighting Mohammad Ali for the throne of the Carnatic.It was a troubled time for Madras and its inhabitants, particularly for those like Pachaiyappa who had no money.

Worse was to come in the coming years.For, in 1767, the Mysore cavalry of Hyder Ali raided Madras for the first time and, two years later, for the second time.The Mysoreans almost caught the Governor of Madras by surprise.He was in the old Government House, by the Cooum, and escaped only because, by accident, a boat happened to be moored on the river.What the two invasions did to the Carnatic is embalmed for ever in the famous passage in Edmund Burke’s speech in the British House of Commons on the Nawab’s debts.For long years, the grim memory survived among the people.Pachaiyappa was to live through the time of terror.

The times were out of joint mainly because the Mughal empire was collapsing, and there was no firm central control. Following Aurangzeb’s death in 1707, which was followed by the inevitable war of succession among his sons, and following the devastating invasions of Nadir shah and Ahmed Shah Abdali, the provinces of the empire were breaking away from Delhi. In the Deccan Asaf Jan had or rather the fiction, was that the Nizam owed allegiance to the Mughal emperor in Delhi, and that the Nawab of the Carnatic similarly owed fealty to the Nizam. In fact, the Nizam was virtually independent of the emperor and, likewise, the Nawab of the Nizam, only that the Nawab’s independence was being challenged and, finally, was subverted by the growing British power. The British, who built Fort St.George in the middle of the seventeenth century, were waxing as a result their success over the French and also as a result of the Nawab’s weakness. It was as his champion against his challenger and would-be supplanter, Chanda Sahed, that they were establishing themselves.Day by day the Nawab came to depend on them for his throne. The British exacted their price for their help, and it was ruinous. The Nawab ahd to borrow money wherever he could in order to satisfy them.

This involved him in enormous difficulties. He borrowed from practically every Briton, official and non-official, in Madras of any note or none and promised them ruinous interest. After a time, forged bonds supposedly of his began to circulate, and all was confusion. The Nawab, always at his wit’s end for ready money, would auction the revenues of his territories; that is, sell to the highest bidder the right to collect land and other taxes from the cultivators. The tax farmer undertook to pay a certain amount of money to the Nawab. He was free to exact from the farmer as much money as he could and in what manner he pleased. The farmer was at his mercy. Little wonder that the country was groaning under the oppression.

At the time Pachaiyappa came to Madras, the British territorial possessions in south India were confined to the Northern Cicars, the Jaghire district, and the commercial “factories” on the coast. The Jaghire district was Chengalpattu district, so named because the Nawab had given it to the British as a jaghir. Conditions here were quite miserable. William Place, a Collector of the district (who is associated with the famous Madurantakam tank incident) said after Hyder Ali’s invasions, “Hardly any signs were left in money parts of the country of its having been inhabited by human beings than the bones of the bodies that had been massacred; or the naked walls of the houses, choultries and temples, which had been burnt. To the havoc of war succeeded the affliction of famine, and the emigrations arising from successive calamities nearly depopulated the districts”.

Thanjavur district, with the fortunes of which Pachaiyappa was to be closely connected for some years, was in a better condition. But even there mismanagement by the Rajas had taken its toll. An English observer, Fullarton, was exaggerating when he wrote that everywhere the region was “marked” with the distinguishing features of a desert”. For, the district recovered quite remarkably after the devastations. Still, it did not escape scatheless.

Thanjavur district, with the fortunes of which Pachaiyappa was to be closely connected for some years, was in a better condition. But even there mismanagement by the Rajas had taken its toll. An English observer, Fullarton, was exaggerating when he wrote that everywhere the region was “marked” with the distinguishing features of a desert”. For, the district recovered quite remarkably after the devastations. Still, it did not escape scatheless.

Thanjavur suffered, in addition to the common disasters of the Carnatic, from its Raja Raja’s military weakness. The British bullied and cajoled the Nawab, and the Nawab bullied the Raja. The Nawab asserted a vague suzerainty over the Raja, from whom he demanded tribute. The Raja evaded paying it as long and ass often as he could. Ultimately, the Nawab resolved to seize Thanjavur, which would prove a rich source of income for him. It was this which led to that celebrated incident in the history of Madras, the arrest of the Governor, Lord Pigot, by some members of his own council and his subsequent death. Pigot, whom the Raja had bribed, with stood the Nawab’s clamour for Thanjavur. The Nawab, who knew the price of every Briton who haunted his durbar, had bribed many members of the Governor’s Council, and these persons went to the extreme length of arresting their own Governor. Ultimately, the Nawab had to disgorge Thanjavur and, still later; in 1801 the British possessed themselves of both the Carnatic and Thanjavur, pensioning off Nawab and Raja.

“Powney” Narayana Pillai, who befriended Pachaiyappa’s family and was responsible for launching him on his career of commercial and financial success, was a dubash. According to Henry Love the author of Vestiges of Old Madras, this word derives from Hindustani ‘dobashi’, a man of two languages, an interpreter or a broker. The British did not know the local languages, and the Indians did not know the local languages, and the Indians did not know English, at least to begin with. An interpreter was necessary in any commercial transaction between the two peoples. Starting as just an interpreter, the dubash gradually became a broker, one who looked after the commercial interests of his European master and was paid for doing so.

The institution dates virtually from the beginning of Madras history. As early as 1686, a Fort St.George Consultation refers to ‘the Chief Dubass’. Nearly every European had his dubash, including the Governor and also the Company in its official capacity. The dubash was a vital element in the commerce and trade of the times.

Thomas Powney, a ‘free merchant’, or a British trader who was not in the Company’s employ and carried on his activities under license from it, belonged to a family that had been connected with Madras since early in the eighteenth century. The first member of the family to appear in the Madras records is John Powney (1683-1740), a sailor. Thomas came to India as a ‘free merchant’ in 1750. He was Mayor of Madras in 1764. He was living in the fort in 1772 and appears in the Madras records twice; in 1775 as one of the merchants who petitioned the Government for a regular postal sitting in the jury at the inquest on Lord Pigot, following his sensational arrest. It is clear that Thomas Powney was a leading merchant in Madras at the time.

Narayana Pillai found employment for Pachaiyappa, then fast developing into a shrewd, but never dishonest, commercial agent under one Nicholas, another ‘free merchant’, as dubash. The employer might be Norton Nicholas, who is known in 1754 to have been trading from Madras. He used to travel frequently in the southern districts for goods to export to Britain. The young dubash made a small fortune in the course of this business. He entrusted it to Narayana Pillai, his benefactor. Even at this young age he devoted a part of his earnings to religious charity.

The young man married his niece, Ayyalammal daughter of his first sister, Subbammal. He marked the occasion with his first considerable religious benefaction. He had images of Goddess Sivakami and of Sir Bali Nayaka installed in the great Ekambaresvara temple in Kanchipuram and performed the consecration (or kumbabhishekam) of the shrines on a grand scale on March 27, 1774. On the same day he laid the foundation-stone of a kalyana mandapa in the temple. Subsequently, this structure was completed. If, as is very probable, this mandapa is the big one near the inner tank, it was a considerable undertaking. Remarkably enough, the benefactor was only twenty years old.

Two years later, Pachaiyappa set up as a revenue farmer in Chengalpattu district and laid the foundations of his enormous fortune. In fact, he undertook so many other responsibilities also that it is amazing to realize that the master financier and merchant prince was just twenty-two years old. The precociousness is unparalleled in the commercial history of modern India. In addition to farming revenue in Chengalpattu district, particularly in Pundamalli, Tripassur and some other parghanas, Pachaiyappa entered into agreements with the Nawab’s officers and with British “free” merchants over payments due on inam lands, disbursement of salaries to the Nawab’s employees, meeting claims on bonds. There were many other kinds of transaction for which the incredible young man assumed responsibility. He also entered into agreements with the farmers of some taluks, and supplied huge quantities of paddy to the Company. As if all this were not enough, he also held the agency business between the Nawab’s officers and some British merchants in all these extensive transactions he was assisted by Pungathur Chengalvaraya Mudaliar and Dharmaraya Mudaliar.

One might think that the young merchant and agent had taken too much on himself. But this was not all. Chengalpattu district, where he was now active, had gone though some bad times. The Nawab had given it to the British, but for some seventeen years, from 1763 to 1780, he rented it from them at a cost of 3,68,350 pagodas. When the second Mysore was broke out in 1780, the Madras Government took over the district and placed it under the Committee of Assigned Revenues. The committee made arrangements with several renters to collect the revenue. Pachaiyappa was one of these.

In parenthesis, it is necessary to explain the state of the currency at the time. The chaotic conditions helped money changers, or shroffs, make much money for themselves. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, there were in the Carnatic some twenty-two mints under the Nawab’s control and some more under the British, the French and the Dutch. The Nawab’s leading mints were in Kovalam, Santhome and Arcot. The British had set up theirs in Fort St.George and Fort St.David (Cuddalore), the French in Pondicherry, the Dutch in Pulicat. All these mints issued coins. The principal variety was the pagoda. There were two leading types of this, one for use in the Carnatic, the other in the Northern Circars. Wholesale transactions were settled with bags of pagodas. The shroffs usually circulated pagodas in bags of a thousand each. By 1720, the Nawab’s mints began issuing coins of lower tough than usual. They made more pagodas or rupees, another coin introduced into the carnatic at the end of the seventeenths century and used mainly to pay the Nawab’s troops, out of the same quantity of silver or gold than the Company mints did. For example, the Nawab’s mints in Santhome and Arcot made Rs.266 and fourteen annas out of every hundred ounces of silver, whereas the company mints made Rs.257 and seven annas. This helped the merchant to obtain nine rupees and seven annas more for his hundred ounces of silver at the Nawab’s mints than at the Company’s. The same situation obtained with gold. The natural result was that the merchants preferred to coin their bullion with the Nawab and, in consequence, currency in the Carnatic was progressively debased in the period between 1720 and 1740. In 1720, the pagoda had eight and five eight parts out of ten in fine gold. This proportion fell even to just five.The regulations were ignored with such impunity that the mints coined pagodas of whatever “touch”, as the expression went, the proprietor of the bullion asked for. At one time the Madras shroffs were ordered not to seal up any pagoda of a lower ‘touch’ than eight and one fortieth. But they ignored the order with impunity and sealed up pagodas of much inferior “touch”. Finally, the Company began minting pagodas of fitness of eight parts. This was the star pagoda, so called because it bore a star on the reverse. It was the standard coin in south India until the early part of the nineteenth century. It was worth Rs.3.50. The ordinary pagoda was exchanged for three rupees. The silver rupee was, by a proclamation dated January 7, 1818, declared the standard coin in the Madras Presidency.

Farming the revenue was very profitable especially if the renter was without conscience, cruel and greedy. How much money he could exact for himself more than the amount he had contracted to pay the Company depended upon how efficient his engines of extortion from the poor peasants were. To do them justice, they were usually efficient to the point of ruthlessness. But experience in revenue matters was also required to the tax farmers, and most of them lacked it. Besides, the Company would demand large advances from them, and theses they could not pay. In the result, most of them defaulted in the third or fourth year of the lease. The Company deprived them of their estates and even imprisoned them. Renter of the Company was no sinecure.But Pachaiyappa, for one, never defaulted. He was as shrewd at business as he was pious and charitable at heart. He made it a principle always to be honest. This earned him the esteem of all those with whom he had dealings. At the end of this period, he emerged as the foremost of the dubashes in the Madras Presidency. He was senior dubash to Robert Joseph Sulivan.

Sulivan, One of the many persons of that name (there were at least four of them in the Company’s service in the Madras Presidency in the eighteenth century, John, Stephen, and John Stewart, in addition to Richard Joseph) jointed the Company’s service in 1768 and subsequently became “Secretary in the Military Department, Judge Advocate-General and Translator”. He was also Resident at the Nawab’s court. Till the beginning of the nineteenth century Government officials in Madras could also trade privately and carry on other activities. The Nawab sent Sulivan in March 1781, as his representative to the Governor General in Calcutta, Warren Hastings, with complaints against Lord Macartney, the Governor of Madras, mainly over Thanjavur and the assignment of some districts which he had made to the Company. Though Sulivan did not achieve all of the Nawab’s aims, he was fairly successful. But that was not wholly due to his diplomatic skill. Warren Hastings disliked Macartney, fearing that the handsome and influential nobleman might replace him as Governor-General. Personal prejudice was an important factor in the dealings of eminent Britons in India in public affairs at the time. Hastings was pleased at the opportunity of doing Macartney an ill turn.

There was another Sulivan, named John among British “free merchants” in Madras at this time. Actually, he had arrived in Madras in 1765 as a civil servant.He was then seventeen years old. (There were a number of what would toady seem incredibly young men in the Company’s civil and military services at the time. Pachaiyappa, himself also young, would not have suffered the pangs of any “generation gap”). He was, like his other British contemporaries, allowed to trade as a ‘free merchant’. In this capacity he tendered for a hospital proposed in Madras in 1771. During the closing stages of the second Mysore war (1780-1784) he was appointed General Superintendent of affairs in the southern districts of the Madras Presidency. Pachaiyappa helped him discharge his duties there. He was by his side till 1785, when the assignment ended. For some time, Pachaiyappa was active farther south, as agent to Colonel William Fullarton, who had been ordered to suppress the many palayakkars who had not reconciled themselves to British control. In his book, A view of the English Interests in India. Fullarton pays u tribute to his Indian colleague. His “earnestness of purpose, persuasive power, and faculty for organization and the success that attended his work on that occasion not only won him the approbation of the authorities but also made a favorable impression calculated to do him ultimately a much larger amount of substantial good”. Remarkably precocious, Pachaiyappa had, at this young age, many of the qualities that usually go with wise old age.

It was now that Pachaiyappa turned his attention to affairs in Thanjavur which were to engross him till his untimely death in 1794, at the age of only forty. Ekoji, or Vyankoji, a half brother of the great Shivaji, had set up the Maratha dynasty in Thanjavur in 1676, or thereabouts. He ruled till 1683. His successor, Shaji (1684-1712), was a man of parts; scholar, linguist, dramatist and patron of the scholars who flourished at his court and his kingdom. Sarabhoji I (1712-1728) and Tukkoji (1728-1736), both of them his brothers, continued his traditions. But there was anarchy following the latter’s death. Pratap Singh (1739-1763), who quelled the anarchy, was a strong ruler. His reign coincided with the Carnatic wars which were ostensibly fought between Mohammed Ali and Chanda Saheb for the Nawabi of the Carnatic, but really between the British and the French. Thanjavur was a rich kingdom, but a week one, on easy prey to enemies. On one occasion, when the French and Chanda Saheb were besieging Thanjavur, the defenders withdrew from the battlements for their mid-day meal and were quietly digesting it when the besiegers less concerned about creature comforts during a war successfully stormed the fort. The old Maratha hardihood had disappeared in enervating luxury.

Nevertheless, Pratap Singh contrived to hold his own, to a greater or lesser extent, in the murderous politics of the day. The Rajas, already involved in the wars of the foreigners and their indigenous clients, carried on one of their own, with the Setupathis of Ramanathapuram. Their fortunes fluctuated. But, on the whole, the waiting foreigner was the only one to profit. With Pratap Singh’s death, the kingdom fell into a decline under his successors and was virtually extinguished in 1801, though it survived nominally and as pensioners of the rampaging British till 1855.

It was with Amar Singh (1787-1798) that Pachaiyappa had to deal. Tuljaji (1763-1787) had succeeded Pratap Singh to a hopeless legacy of war, internal dissensions and debilitating luxury. The Nawab, pretending a claim of suzerainty over Thanjavur, invaded it in 1771. Tuljaji was compelled to buy him off. He signed a humiliating treaty whereby about thirty-two lakhs of pagodas were paid as war expenses in addition to eight lakhs as arrears of tribute and two districts were ceded. Soon after this, the Raja had to buy off Hyder Ali, who threatened on invasion, and Hyder’s invasions were no joke. The Raja not fulfilling the treaty with the Nawab, the latter launched another invasion, again with the Nawab, the latter launched another invasion again with the help of the British, and had him imprisoned. Quartered on the hapless peasants, the Nawab’s harpies, the most notorious of whom was Paul Benfield, bled the kingdom white. In 1775, as much as eighty-one lakhs of rupees were extorte; the highest amount collected till then has been only fifty-seven and a half lakhs of rupees in 1761. Subsequently, the Raja was released from prison and restored to the throne. But this was followed by an invasion by Hyder Ali, which could not be averted. The people suffered as they had never before.

With the next ruler, Amar Singh, Pachaiyappa had extensive financial dealings. Amar Singh was an illegitimate son of Pratap Singh. It was Tuljaji’s dying wish that Amar Singh should be Regent for his own adopted son, Sarabhoji II. The British forced onerous treaties on the Regent. He had to agree to set apart two-fifths of the kingdom’s revenues to meet the expenses of the military peace-time establishment, and for this he had also to give territorial security. The amount would be doubled if war came. In addition, the Regent was to pay four lakhs of pagodas as annual tribute to the Company and three lakhs towards debts due to the Nawab. These charges were so heavey that the Regent could not possibly meet them. In addition, his place as Regent was insecure, and he was extravagant.

In a few years the Regent fell into arrears. In 1790-91 the Company wrested from him the right to collect taxes. This brought to relief to the harassed peasants. The Company’s dubashes were equally rapacious, their aim being to make as much money as possible in as short a time as possible. It was said that an unscrupulous dubash m ight make two to four lakhs in ten to fifteen years.

In 1792, after the third Mysore war, the Company imposed another onerous treaty on the Regent. He had to pay a part of the expenses of the military force that the Company maintained chiefly in the forts. In wartime the Company could virtually take over the kingdom, allowing the Raja a lakh of pagodas and one-fifth of the net revenue. If the Regent did not pay the tribute and subsidy in time, the Company could collect the amount for itself. It was against this background that Pachaiyappa’s activities in Thanjavur should be considered. It is a wonder that he could keep his hands clean in this welter of corruption and fraud, coercion and oppression.

Amar Singh wished to be made Raja in his own right, and not a mere Regent. On his petitions, the Governor-General, Lord Cornwallis, directed the Governor of Madras, Sir Archibald Campbell, to inquire into the circumstances under which Sarabhoji had been adopted by Tuljaji.Campbell went to Thanjavur in April 1787, and asked twelve pandits for their opinion on the legality of the adoption. These pandits had already been bribed by Amar Singh, and they unanimously said that “the adoption of Sarabhoji was illegal and invalid, and the right of Amar Singh to the throne clear and undoubted”. Campbell placed Amar Singh on the throne.

There are diametrically opposed views on the nature of Amar Singh’s administration. According to far from disinterested evidence, it was a tyranny and a corruption. It was alleged that the sar-i-khel, the equivalent of Chief Justice, sold justice and that six rapacious individuals to whom the management of the kingdom was given tyrannized over the people and misappropriated the State revenues. But another line of evidence suggests that Amar Singh was a good and humane ruler. The demands made on him by the British were so many and so onerous that he could not possibly meet them. His treasury was nearly always empty.

Sarabhoji’s partisans set up a clamour. The British again consulted the pandits. This time they pronounced in favour of Sarabhoji. Accordingly the British deposed Amar Singh and place Sarabhoji on the throne. But this was a pretence. In the year after his accession, in 1799, Sarabhoji was ‘induced’ to become a pensioner of the British. He resigned to the British the administration of the kingdom in return for a pension and jurisdiction over Thanjavur town and Vallam. He is usually praised for his patronage of literature and the arts and for his own attainments. The British gave him ample means and leisure to indulge these.

Pachaiyappa went to live in Thanjavur in 1784, when Tuljaji, on the throne, had three more years to live. Both Tuljaji and Amar Singh, the latter only even more, following the treaties the British had imposed on them, had onerous financial dealings with the Madras Government. Pachaiyappa acted as something like their financial agent. He was also the Company’s dubash in making remittance of the annual tribute and other amount due in proper specie. He is said to have received a discount of ten or twenty per cent on these transaction. He also helped the chiefs in the southern districts in having their financial dealings with the Madras Government settled equitably. He was in high favour at the Thanjavur durbar not only for his wealth but also for his probity. He is depicted in court dress in a painting in the Thanjavur palace, from which an oil painting was made by a British artist later.

In 1787, Campbell place Pachaiyappa in charge of collecting revenue in Thanjavur and ensuring the regular payment of the annual tribute Amar Singh, who was much impressed by the integrity and business ability of Pachaiyappa, also invited him to take up the task. At this time Pachaiyappa was in Madras, apparently staying at the house in what used to be called Pagoda Street, in Komalesvaranpet, now called Harris Road, which, during his life-time, was famous as the centre of his truly regal philanthropy and piety.

He appears to have been led to build his residence in that quarter of Madras (According to Mr.W.S.Krishnaswami Nayudu, in writing a life of a forbear of his, swamy Naik, who live in the eighteenth century, Pachaiyappa’s house adjoined Swamy Naik’s and was, in 1951, when the biography appeared, numbered 26) by the example of a mentor of his, Kuzhandai Veeraperumal Pillai, a magnate of the times. Since Indian magnates recur in this account, the reader will realize that contrary to the general notion, Madras history in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was not the history of the European residents alone, but that quite a number of prominent Indians too were living there. Pachaiyappa was undoubtedly the greatest of them all, but he was by no means the only one.

Veeraperumal Pillai was an intimate friend of Pachaiyappa’s. He acted for Campbell, Sir Thomas Rumbold and Lord Macartney, all Governors of Madras, in their private commercial transactions. He was the proprietor of the srotriem estate of Sriharikota. He spent his income from this village of temples and in charity. He was living in a mansion on the banks of the Cooum, but on the eastern side, in sunkuvar Agraharam, in Chintadripet. The poor Cooum, so much an object of detestation today for its smelliness, was, two centuries age, venerated under the fine name of ‘Kshira Nadhi’, or the ‘River of Milk’, particularly at the spot where it runs north and thus becomes a ‘uttaravahini’. Wishing to live near his friend, Pachaiyappa built his own residence by the western bank of the sacred river, in Komalesvarnpet.

The locality presented a very different appearance from what it does today. There were many mansions hereabouts, where lived some of the first men of the day in Madras. These were built in the traditional Indian style. Pachaiyappa made his home virtually a temple. Pilgrims and scholars thronged it in order to benefit from his magnificent bountifulness. He spread a table every day for hundreds of the poor and often himself ate with them neither demanding nor receiving any special dishes. Every day he listened to expositions of the scriptures. Before going to bed, he also listened to bhajans. He appears to havebenn particularly fond of sekkizhar’s peria puranam. He celebrated the birthdays of the sixty-three Nayanmars. He set up charities in the temple of Komalesvarar, in Komalesvaranpet.

Besides, Pachaiyappa worshipped at many centres of pilgrimage and gave large benefactions to the temples. He built choultries at many places along the old pilgrim route to Rameswaram which, before the extension of the railway, passed by vedaranyam and the Thanjavur coast. He erected mathas at many places in Thanjavur district.

He had special veneration for Lord Nataraja in Chidambaram. It was during this period, when he was living partly in Thanjavur and partly in Madras, that he made truly magnificent gifts to his temple. Perhaps, only the imperial Cholas before him had been so munificent. He gave large quantities of jewellery and huge amounts of money, Remarkably enough, and this is an indication of the fact that he wished to reform the abuses that had crept into society, he insisted that the degrading nautches should not be held in the temple’s festivities. There was some resistance to his caveat. But, with the help of another friend of his, Manali Chinniah Mudaliar, a scion of the Manali family which has played a part in the early history of Madras, he overcame it. He built a ratha for the Lord and erected the existing ratha stand. On June 28, 1791, he initiated the temple’s second annual festival, after the celebrated Ardra festival, usually held in December. This is the Ani Thriman janam. He got the trustees of the Govindaraja shrine in the temple to agree to his festival. He also attempted to reconcile them with the authorities of the Nataraja shrine. It should be remembered that the magnificent benefactor was only thirty seven years old.

At about this time Pachaiyappa committed an indiscretion. For, so his second marriage should be considered. He was actuated by good motives. He had no issue from his first marriage, and he was haunted by the thought that afflicts Hindus that he had no son to perform his obsequies. That was why he married a “woman from Vedaranyam”, as she is frequently called in the records. Her name was Palani Ammal. She and the first wife were at loggerheads and they lived in separate houses. She gave birth to a girl. But the child died within a few months of its mother’s death which itself occurred soon after Pachaiyappa passed away in 1794. Pachaiyappa had no joy of this marriage. In his will he did not provide much of his property to either wife or his daughter. He willed it to charities.

All this was in the future. In the meantime, Pachaiyappa, when asked to go to Thanjavur to help bring some order out of the chaotic financial situation there, was reluctant to do so. But William Petrie, a civil servant of rank, who subsequently acted as Governor of Madras for three months in 1807, and who had been appointed to regulate the financial matters in Thanjavur, induced him to accompany him. He then left, accompanied by a certain d’Souza. They succeeded in arranging matters in Thanjavur. He gave the Raja, in a personal transaction, a loan of a lakh of pagodas so that he could repay a debt long owing to the Company.

It need hardly be said that, while temptation to chicanery and fraud abounded, Pachaiyappa would have none of it. But there were some Indians, like Subba Rao and Chinniah Mudaliar, who exploited the situation for all they were worth. They would lend huge sums to the Raja on the security of pledged villages at exorbitant price. Some of the Europeans active in Thanjavur, themselves far from paragons of rectitude, petitioned the Government, alleging that Pachaiyappa, Subba Ral and Chinniah Mudaliar wre extorting money from the Raja and that their aim was to keep him perpetually dependent on them for money. They said that the three Indians were obtaining leases of innumerable villages from the Raja on easy terms, realizing the dues from the villages in paddy, and selling the paddy at unconscionable prices. They demanded that these three be sent back to Madras to answer the charges.

The obliging Madras Government ordered them to leave Thanjavur. Pachaiyappa returned to Madras and, through Petrie, protested against the charges leveled against him. He said that never had he committed any fraud and that nobody that complained against him as many had against Subba Rao and Chinniah Mudaliar. The Raja still owed him fifty thousand pagodas and, if he was not in Thanjavur, he would find it difficult to recover that loan. It was highly irregular that he should have been asked to return to Madras when, initially he had gone to Thanjavur very reluctantly and only at the repeated requests of Campbell. On his return to Madras, Pachaiyappa was dubash to a son of Robert Joseph Sulivan.

As was to be expected, the official inquiry into Pachaiyappa’s financial dealings in Thanjavur showed that his conduct had been irreproachable. The malice of his European detractors was thwarted, and he returned to Thanjavur. He had the more reason to do so because, when in Madras, he had suffered an attack of paralysis. It was not serious enough to incapacitate him, and he could attend to business. He though that Thanjavur’s dry climate would uit him better than the moist climate of Madras. Before leaving for Thanjavur, he secured for Ayya Pillai, the son of his patron, ‘Powney’ Narayana Pillai, the lucrative post of dubah to Joseph Sulivan. He repaid in full measure the abounding goodness the great merchant had shown him from his early days.

It was in June, 1792, that Pachaiyappa returned to Thanjavur. He resumed his banking business for the Raja.He became friends with James Strange, who was the British representative at the court as paymaster in Thanjavur. Like nearly every European who had dealings with him, Strange had the highest opinion of Pachaiyappa. His sense of gratitude for ‘Powney’ Narayana pillai was so strong that it was against him that he drew all his hundis on Madras. He also made him his agent in Madras, and it was through him that he made all the payments due from him to the Government and to other parties. All this made for a good income for Narayana Pillai.

But illness was crowding in on Pachaiyappa.He underwent treatment for his paralytic stroke. This brought him some relief, but he began to suffer from stomach and other ailments. He realised that this end was not far off, though he was only forty years old. He went to Kumbakonam in order to complete building a choultry he had begun to erect opposite to an agraharam he had already set up. On March 22, 1794, he wrote his will. The poor man did not know it, but this will was to involve his family in protracted litigation.

In this will Pachaiyappa directed that, should his health deteriorate and the worst happen, ‘Powney’ Narayana Pillai and his son, Ayya Pillai, should act as his testators. Out of the interest from a lakh of pagodas which he had given as loan he arected that services should be performed in the temples from Kashi to Rameswaram which he had selected. At present work was proceeding on the eastern gopura of the Chidambaram Sri Sabapathi temple with the 11,300 pagodas entrusted to Puvalur Iyan Chetty. When this sum was expended, money available over and above the lakh of pagodas which, out of his own earnings, he had set apart for “Siva dharma”, should be spent on completing that gopura, whatever amount was wanted, 20,000 pagodas, 30,000 pagodas. The testators were to give his ‘gurukkal’ a thousand pagodas with which to build a house for himself, and another thousand the interest from which he was to use for his household expenses. He was, therefore, to be given two thousand pagodas in all.

Vinayakamurthi Pillai, who had been writing his accounts for long years, was to be given a thousand pagodas with the instruction that he was to spend the interest on this sum on Siva puja. The testators should every month send interest on 1,100 pagodas to the Pandarasannidhis in Tiruvaiyar for the expenses of ‘Mahesvara Puja’. Apart from the jewels given to the ‘Vedaranyam woman’, whom he had married as his second wife, 5,000 chakrams was to be given when her child became five of six years old for her marriage expenses. Interest on five thousand pagodas, to be put out to interest somewhere, was to be given to his sister’s son, Muthiah, a ‘senseless boy’. Ten thousand pagodas in cash was to be given to Ayya Pillai, the son of Narayana Pillai, and to his children. The rest o this property was to be placed under the control of Narayana Pillai, who was to be guided by the advice of Pachaiyappa’s sister and first wife.

The will was witnessed by Anna Gurukkal and Ramalinga Pillai.Pachaiyappa signed the will ‘Ka.V.Pachaiyappan’. The letter “V” is in English, the rest in Tamil.

Two days after signing this will, on March 24, Pachaiyappa wrote a letter to Narayana Pillai.He said that he was slightly better, but that Lord Siva’s will was still to be known. Narayana Pillai was not to be discouraged by anything. It looked as if the Lord’s grace would set every thing right.

He had borrowed two thousand pagodas from Varada Pillai when he had first come to Madras. He had immediately returned a thousand pagodas. Narayana Pillai was to tell Varada Pillai that the other thousand would be returned. Even if Pachaiyappa were to pass away, the principal was to be returned with interest. This was the last letter Pachaiyappa was to write.

Soon after writing the letter, Pachaiyappa wished to go to Tiruvaiyar. An old belief was that to pass away in that sacred and historic place was equal in sanctity to dying in Kashi itself. He passed away there on Monday, March 31, 1794 (in the Tamil calendar 21, Panguni, Pramadisa year on Amavasya day).

Thus ended a life that was noble to the last minute. The times were disastrously out of joint. The Carnatic was a welter of decay of moral values. It was the age of the freebooter and of the marauder. The strong tyrannized over the weak, the crafty cheated the simple. Yet, in the midst of all this, Pachaiyappa did not succumb to temptation. Riches came to him, and he spent them nobly. The Chola kings apart, there has been no more splendid benefactor of religion in Tamil history. Traditionally, mighty temple gopuras were built by the monarch or the nobleman. Pachaiyappa was one of the few commoners in the history of the Tamil temple to raise, or renovate, a huge gopura and that in Chidambaram, the most sacred and sanctified of Saiva temples in Tamil Nadu.

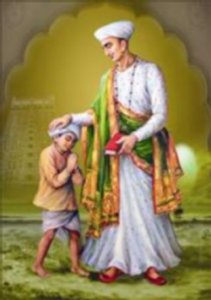

Pachaiyappa had an oval face, with broad eyes. He was tall in stature, with long hands that reached down to the knees, a feature considered in olden days a mark of greatness. His forehead was broad, and he had an aquiline nose. He usually wore a white muslin robe, a lace shawl thrown over the shoulders, a turban of the style customary in his time, and a fine coloured cummerbund, or girdle. On ceremonious occasions he loved to deck himself with ornaments; big ear-rings, emerald ear-drops, bangles set with diamonds and rubies, necklaces of pearls and other precious stones, several finger rings. Pachaiyappa stands ineffity, in an attitude of worship, in a niche on the southern side of the entry-way in the eastern gopura in Chidambaram. An inscription on the base identifies him.He is represented as a slender figure with a moustache standing with his hands in anjali.Subbammal stands in another niche nearby.

A figure of Pachaiyappa in ceremonial dress appears in a painting of Amar Singh’s durbar in the Thanjavur palace. A full-length painting was made by an English artist, Ramsay Reinagle, inLondon in 1850.

Pachaiyappa lives in the hearts of the devout and of those whom his educational charities helped in the struggle of life. But it was to be wearily long years before his will could be implemented aright.

Komalesvaranpet Srinivasa Pillai who, after only “Powney” Narayana Pillai, must be considered the most effective upholder of Pachaiyappa’s name, fame and memory, wrote a life of him in Tamil but “in the English manner”‘ after gathering materials at many places. At the fiftieth anniversary of Pachaiyappa’s College, Vembakkam Krishnamachariar, a Trustee, wrote a condensed translation of this into English and published it along with Tamil poems written for earlier anniversaries of Pachaiyappa. The Tamil work, very scarce even then, was republished along with the old and with new poems in 1911 by Pakkam Rajaratna Mudaliar, then Chairman of the Trustees.